If ever a label had its own aesthetic, it was Emanem. “My magnum opus is the Emanem label” said the main man Martin Davidson For any record label of any genre which seeks to get across its ideas or ideology, the rigour and clarity with which Emanem operated provides an exemplary model.

Davidson’s sudden death in December 2023 finally put a full stop to his label activities, which had been gracefully winding down for a few years since he moved to Spain with partner Madelaine in the 2010s. A pair of events at Cafe Oto and The Vortex (today at time of posting) gives a chance to reflect on the unique language of the label, and pay dues to a project which many label will owe a debt to for years to come, whether they know it or not.

Start with the discs themselves: neat white CDs, Arial-style font, chunky catalogue numbers on the spine, and text in bold or CAPITALS the only concession to flair or variation. Serious and sober, in Davidson’s image. Expanses of white on the covers and in the booklets have obvious resonance with the music itself, which is spare, sharp European improvisation, where the players have to find a home within the openness and space. Emanem presented a pristine blank slate for the players to do their thing, and I file it mentally alongside other rigorous ‘artists decide’ labels such as ESP-Disk’ and and Another Timbre . For a listener such as myself, these white CDs held the promise of uncut radical sound straight from the source.

But Davidson had a healthy scepticism of what critics thought, to such an extent he made his own brilliantly sardonic dictionary of music terms which is still provocative: “jazz-rock: a rest home for certain retired jazz musicians.” His perspective on CDs is a necessary read for anyone who takes sound seriously, and a timely corrective to vinyl fetishism: “In the 1990s I was able to issue music on CDs, and it was such a relief: no surface noise, no SCP, no print-through (pre- and post-echo), no rumble, and no distortion caused by loud sections and phase problems. It was also possible to have a much larger dynamic range between loud and soft sections, rather than have everything compressed to a small dynamic range.”

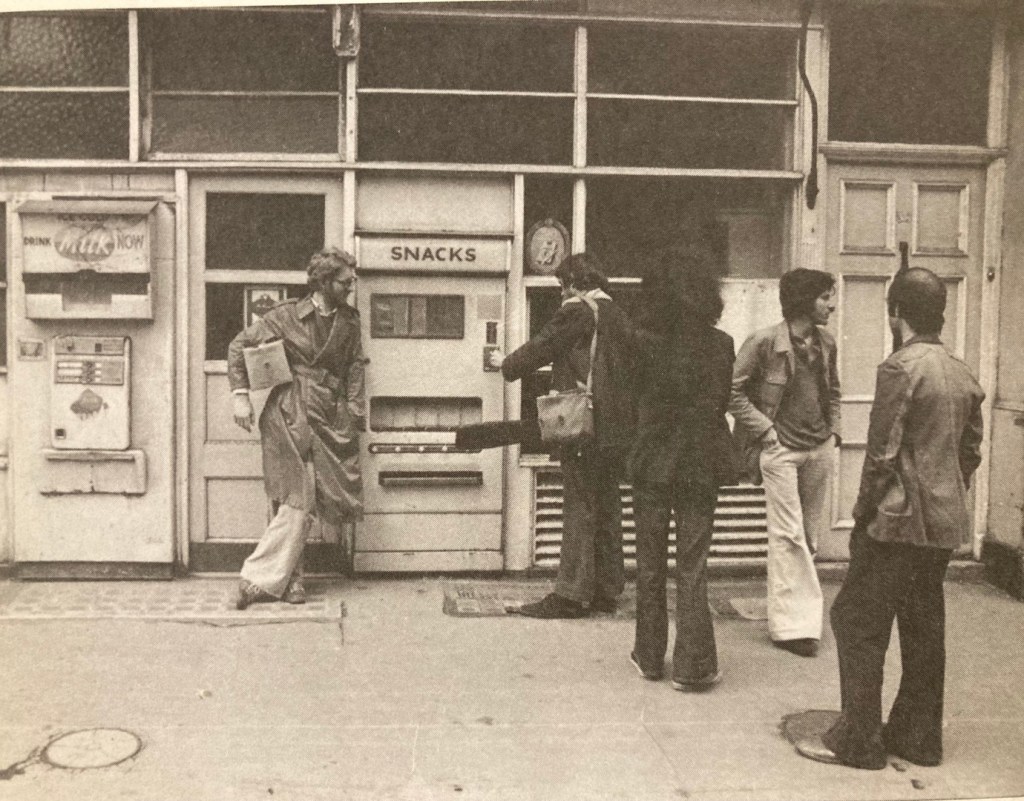

Emanem’s aesthetic was to present live musical communication in all its rich complexity, “unadulterated new music for people who like new music unadulterated”. He supposedly pondered an alternative name of Radical Atheist Culture, but found it an ill-fit with the open ethos of the label. Davidson used to troop around London back in the mid-70s with a Revox tape tecorder groups to venues like London’s Unity Theatre, capturing players such as the quintet of Steve Beresford, John Russell, Garry Todd, Dave Solomon and Nigel Coombes (above) heard in various configurations on Teatime (originally an Incus LP, reissued by Davidson). I’d love to know at what point he decided this music must be captured for posterity, and why he took it upon himself to record it so exhaustively.

Davidson didn’t like applause, which sounds contrary, but was simply a matter of rigour. “Applause in the middle of a piece drowns out the next part of the music, while applause at the end destroys the ensuing silence which is often an integral part of the music.” Emanem recordings do a remarkable job of presenting performances as events with their own internal integrity, in all their own crystalline beauty. Another Emamen recording, the tremendous Vortices And Angles featured a recording of John Butcher and Rhodri Davies by Tim Fletcher, and it does a remarkable job of recording close to the instruments so that they appear awesomely huge and the rest of the world melts away.

All this means that Emanem made an art of presenting live group interplay on disc, all of which will stand the test of time. The care and attention to balance shines through: Three Pianos with Beresford, Pat Thomas and Veryan Weston was recorded in the relatively high end space of Gateway Studios; Davidson sometimes went as far as to remix albums like Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s Karyobin to strive for a perfectly balanced sound. It’s this that makes their catalogue (which one hopes will remain in print) one of the great resources of experimental British music. The perfect place to properly appreciate his wares would be at the now extinct Freedom Of The City festival, where Davidson would take over a couple of merch tables with his entire catalogue, expanses of white CDs, all of which you could take a chance on.

I’m a fan of footnotes – who isn’t? – which might be why Emanem CDs hold such fascination. The CD booklets and the Emanem website read like a series of rigorous footnotes interrogating a historical event from multiple angles. Memories are added from different figures – often, all of the players involved in a particular session. It’s an ongoing process of clarification and distillation which might well feel pedantic if the end result was not so pure and strong.

Maybe the fastidious dedication to live performance gave a natural arc to the label’s lifespan, because by the 2010s, many of the luminaries of UK improvisation had recorded multiple times for the label, and in the internet age, live recordings of groups started to find an alternative home online. Emanem’s work was probably done. When Emanem would reissue earlier albums in updated CD additions, as they did for many friendly labels such as Incus and Acta, Davidson would often add extra recordings from a similar era or group of players. Sometimes, this would mean pairing one impressive recording with an inferior one. Sometimes it would puncture the unity of a moment they’d strived hard to capture in the first place. Not everyone wants a CD which runs over an hour just because it can, but he did it his own way. I wonder if Davidson was sitting on so many archive recordings he just couldn’t bear to keep them to himself.

The rigour and exactitude of Emanem – few press releases, press photos, forget about downloads – was never going to be a smash hit. Davidson himself was not in the salesman business. In later years, the Emanem mail order business would go on unofficial hiatus for extended periods. I remember one time back in the 2010s saying to Martin I wanted to place a big order and asking his advice as to how to start an Emanem collection. He never got back to me with the info, but the CDs I bought taught me what I needed. Maybe he knew what he was doing all along.

Photo: East London, mid-1970s: (from left) Beresford, Russell, Coombes, Solomon, Todd (unknown photographer)