The brand new release of a previously unheard Alice Coltrane performance from 1971 is like a gift from the gods. It seems miraculous that a music so personal, even reverential, could have made it to New York’s famous Carnegie Hall, in probably her most important year as an artist.

To consider the personal, Alice’s first three albums were inhabited by a constellation of spirits and the divine. John had died not long before 1968’s A Monastic Trio – he is credited on the line-up of the album (“Ohnedaruth, known as John Coltrane”) and his posthumous voice introduces “Oceanic Beloved” with a prayer. Third album Ptah, The El Daoud is named after an “an Egyptian god – in fact, one of the highest aspects of God”, and describes a “march on to purgatory”. There’s a quality of ritual and pilgrimage to Alice’s music that’s hard to imagine in the formal context of a concert hall.

1971’s Journey In Satchidananda was Alice’s breakout record, in part because of its adventurous instrumentation. Tulsi’s tamboura sets the stage for and runs all the way through the title track, and the instrumentalists play around (rather than over) the drone in a decisive break from the past. The soundscape of “Journey In Satchidananda” – deep, spacious, humid – instantly places the listener in a different place from hard-scrabble pathways of free jazz explored by John in the 1960s. Once heard, the bassline of “Journey In Satchidananda” stays with you for years.

This new artistic direction was evocatively described by Tony Herrington in The Wire 159. In a timely Editor’s Idea, around the time of Impulse!’s 90s reissue programme, he defends the music against critics for whom it was spiced-up with exotic instrumentation and ethnic novelty. “Rather than too much ketchup,” he wrote, “those effects and chants, hovering hypnotically at the edges of the music, signalled: no visa required, providing a point of entry into a music that was otherwise an impenetrable nation-state to the non-initiate.”

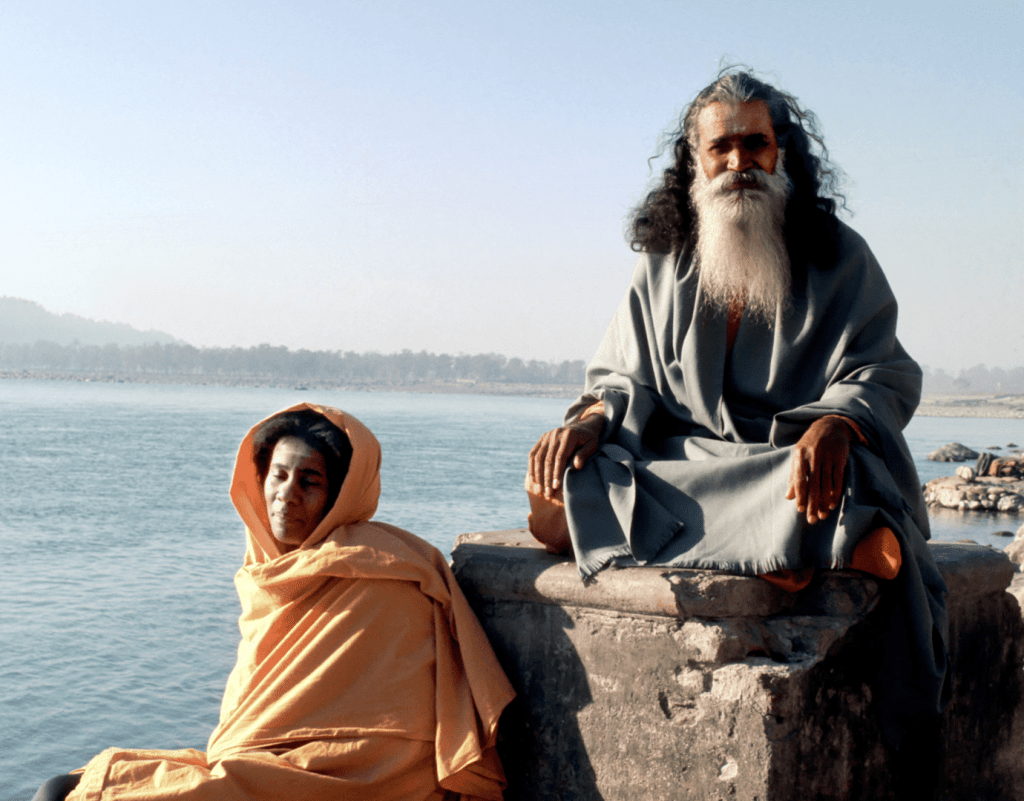

By 1971, Alice had become a citizen of the world, and fallen in with an international spiritual community that is crucial to understanding this new phase of her music. Yoga guru and spiritual advisor Swami Satchidananda had come over to New York from India in 1966 at the invitation of Conrad Rooks. He became a minor celebrity in the years that followed, lecturing at Carnegie Hall in the late 1960s to public acclaim. He became a friend of Alice around the turn of the decade, and after recording the Journey In Satchidananda album in 1971, she joined Swami Satchidananda on an extended leg of his world tour, an itinerary foreshadowed on the album itself in the track “Stop Over Bombay”. According to Swami’s assistant Shanti Norris, they were close companions on the trip through India (the period is discussed in detail in Franya J Berkman’s book Monument Eternal: The Music Of Alice Coltrane). So when Alice played Carnegie Hall in 1971, for a gala benefiting Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga Institute, she was in many ways on familiar territory.

The music contained on The Carnegie Hall Concert – parts of which emerged on a shady release in the 2010s, but the most part of which has remained unreleased – takes the music of Journey In Satchidananda even further out, with two tracks included from that album, alongside two John Coltrane lengthy compositions. Because the studio album laid down such a weighty anchor, this live album – with an unusual line-up of two basses, two drummers and two saxophones plus harmonium, tamboura, and Alice on harp and piano – can dive even deeper. On the live version of the title track, the two basses, playing slower than on the album, provide a gooey, viscous substratum that feels like they stretch the fabric of time.

Alice’s harp playing on “Journey In Satchidananda” is a revelation. Whereas on the studio album, the instrumentalists play around the steady drone of the tamboura, here, around five minutes in, Alice plucks away at tonic and subtonic and higher notes on her harp. It hints at a back and forth movement within the chord structure that’s less evident on the studio version and lends it a bittersweet quality, and gently directs the contributions of the other players.

“Journey In Satchidananda” has the quality of a ghost version or evolved relation of the original. Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp don’t state a solid saxophone theme like on the studio album, instead exploring colours and sub-resonances hinted at in the composition with soft, split, almost flute-like notes. It’s a fluid, flowing performance, a living space, to take the title of John’s posthumous album.

Cecil McBee, in an interview conducted by Franya J Berkman in 2001, described the way Alice would prepare her groups for a recording. “It was very, very spiritual. The lights were low and she had incense and there was not much conversation, dictation or verbalisation about what was to be. The desire of your essence was all very, very tangible. The spiritual, emotional, physical statement of the environment, it was just there.” When Pharoah Sanders died in 2022, I wrote in The Wire 465 that instrumentalist or improvisor was an inadequate description for a musician of his scope – more like “bandleader, session producer and spiritual seer.” Alice Coltrane likewise radically expands the staid old Western idea of what a composer does. Rather than just putting notes on paper, she plans the space, sets the scene, prepares the group, and defines the musical elements at play. As Alice wrote of the title track of Ptah, The El Daoud, it was “more a feeling than a melody”.

The Carnegie Hall Concert is a triumph in its own right, but also causes me to reflect on the idea of the ‘lost album’. This holy grail of marketing terms was dropped repeatedly around the time of John Coltrane’s Both Directions At Once, a solid album from his classic quartet period which was recorded in 1963 and finally issued in 2018. The idea of the ‘lost’ album usually makes me question how lost it really was, or whether it was lost for good reason – are capitalist organisations really be so careless as to lose valuable assets?

But maybe we’ve been looking in the wrong places. The incredible recent John Coltrane/Eric Dolphy discovery Evenings At The Village Gate was discovered at New York Public Library. The Carnegie Hall Concert is released in conjunction with The John & Alice Coltrane Home. There are doubtless other archives that could be explored. If you believe the record industry already has everything under its control, it might underestimate just how strange and diverse the living legacy out there really is.

You can check out “Shiva-Loka” from The Carnegie Hall Concert here.

Photograph: Alice Coltrane and Swami Satchidananda, early 1970s (Satchidananda Ashram/Yogaville/Integral Yoga Archives)