Evaluating the art of Cecil Taylor is like trying to forecast the weather in the middle of a tornado. His playing can be torrential, a storm of piano notes and strikes, and he performed with almost every imaginable type of ensemble over 60 odd years as a bandleader and composer/instigator, even incorporating poetry and dance.

His music was a lot, and so was the way he rolled. He played international festivals rather than local gigs or the loft circuit, performed almost exclusively his own music rather than other people’s, didn’t do smalltalk, and was openly gay in intolerant times. He enjoyed champagne and cocaine and didn’t give a fuck.

Taylor became a titan of 20th century music, but he had to walk through fire to do it. He chose the life of an artist, valuing originality over all else, which made him something of an outsider even in jazz circles – his 1950s ensembles were notorious for putting punters off their drinks and killing the vibe in clubs. Because he was often on the road looking for the next engagement, his music was increasingly created live rather than laid down in the studio for easy consumption at home.

So his art is mercurial and, for some, intimidating. Writing a book on Taylor has sometimes seemed like an impossible assignment, particularly as Taylor, who died in 2018, used to be an unpredictable and stubborn interviewee – at the time of writing, jazz researcher/educator and former WKCR programme director Ben Young has been working on a biography for several years.

Taylor was too much for some, but not for Philip Freeman, who has previously undertaken the comparably epic task of chronicling Miles Davis’s electric period. His immersion in all frequencies of intense music, from metal to jazz to free music, means that not only is he prepared for the deep dive into Taylor’s world, he welcomes the deluge.

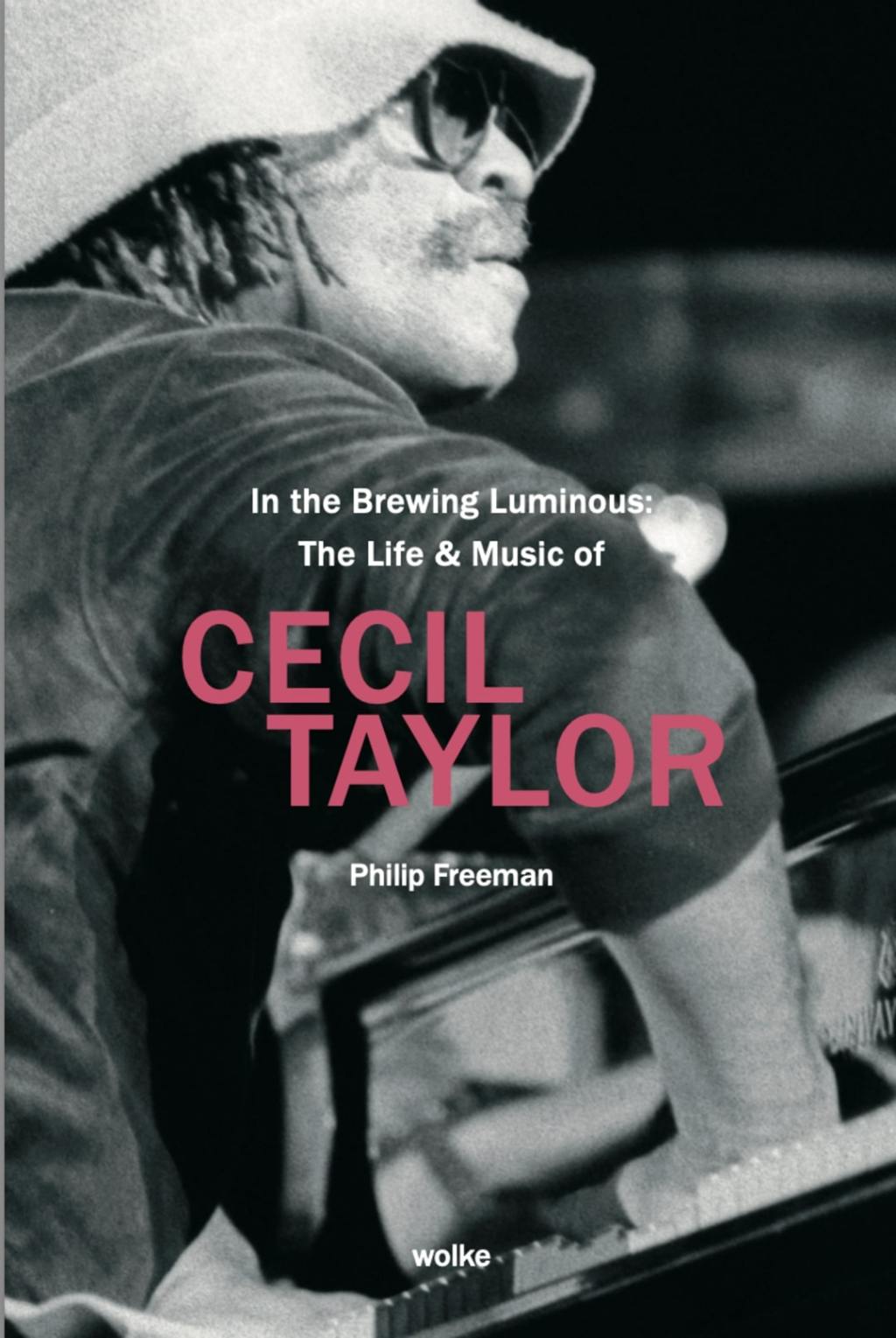

In The Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music Of Cecil Taylor is as complete a picture of his music and philosophy as we could hope for right now.

The book is particularly timely as the internet has helped to make Taylor’s work accessible again. In the final decades of his life, Taylor’s music had started to become an exclusive concern, with his album releases sporadic, limited in numbers, and often punishingly expensive. Head to YouTube, however, and you can find Cecil in his eighties performing in Barcelona and sounding as adventurous and in love with the piano as ever (there’s an odd echo here with someone in the book he shared a stage with, the great Earl Hines, who when he played for French TV in the 1960s was as energetic and imaginative as he ever was with Louis Armstrong). There’s a sensational video of Taylor’s performance upon his acceptance of the major Kyoto art award in 2013, when Taylor roams, vocalises, recites and eventually plays the piano to accompany dancer Min Tanaka. You can even watch his stilted but powerful performance at Ornette Coleman’s funeral, a short piece which nevertheless carries decades of insight and emotion.

Phil was The Wire’s guy on the spot when the Whitney Museum in New York prepared a major retrospective of Taylor’s work back in 2016, bringing together documentation, photographs, scores and ephemera plus several ambitious performances by Taylor and ensemble. He spent a couple of days with Taylor, interviewing and hanging out and listening to him playing. One of Taylor’s quotes in the piece that stuck with me particularly concerned his love for Beyoncé and Rhianna: “singers he evidently regards as masters of their own craft, and whom he seems to love every bit as much as the female vocalists who inspired him when he was younger, like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday.” What seems like a superficial aside is revealing. As Freeman explains in his book, Taylor forcefully asserted his place in the lineage of jazz and Black/Afro-American music, insisting that his wild piano playing was merely the logical extension of where Duke Ellington and Lennie Tristano had gone before.

Freeman sets out at the start of the book that “it does not matter where exactly he lived from year to year, where he worked… or who his romantic partners might have been.” Perhaps this is because those details are hard to come by, but it’s also out of respect to the artist, as “there was always much that Taylor kept to himself”. The focus is solely on the work, and the book starts at the beginning of Taylor’s life and powers through almost a century, documenting the ensembles he formed, the engagements he played, and the recordings he made.

Chronological accounts of great people can get tiring, and a linear trajectory can risk excluding meaningful or resonant themes that lie in the background or are threaded through people’s lives. It might have been interesting, perhaps, to have heard more about how Taylor kept himself solvent in the early days, or some vignettes of the social situations in which he clearly thrived, perhaps even more about how he dressed and carried himself, which is clearly something that was considered carefully.

But the linear approach works for several reasons. Freeman argues that Taylor’s work has been misrepresented as obscure or impenetrable, and discussing each and every one of his artistic projects helps decode crucial relationships with players like saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, and how his ensembles rehearsed to create their distinctive sound worlds. There are insightful passages where Freeman interprets performances through the lens of particular musical personnel, showing how Taylor captured the energy inherent in particular groups of people. This music was magical, but as the book shows, it was the result of hard work.

The arrow-like trajectory also resonates with Taylor’s MO. The book never sits still, is always moving onto the next engagement and project, carrying the energy from one onto the other. Freeman takes Taylor’s art as seriously as the pianist himself, and puts in the hours listening to what by my estimation is at least a couple of hundred recordings of Taylor’s work.

This is a book you want to read with a notebook to hand, so you can jot down some of remarkable sounding recordings – Taylor’s notes “striking like a raindrop on summer asphalt” on Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! Fly! or “coming up with a new idea and examining that from as many angles as he can think of” on Garden. The book exudes a respect for Taylor’s work ethic, and the insights that Freeman gains feel hard-won, too.

Many of Taylor’s key collaborators are now gone, so the new interview material is predominantly confined to the later stages of the book. What Freeman has done instead is to make sure he’s read almost everything, from interviews to sleevenotes to news reports to even university prospectuses. The sheer number of projects and collaborators discussed can be hard to follow, but it lends the project the authority of an oral history. Aspects of it remind me of David Katz’s roots reggae panorama Solid Foundation, which coincidentally is about to be republished in an expanded edition – both are books which are necessary acts of recording and remembering while there is still time.

In a crucial section regarding Taylor’s 70s music, Freeman quotes from an interview with Gary Giddens. “The non-European aspects of the music” have been ignored by many white critics and listeners, Taylor notes. There are eloquent passages describing the magical connection between hearing and playing, and how the European interpolation of symbols and notation between has left music disenchanted. “When the dust settles, he will be remembered as one of America’s greatest artists.” The book makes a solid and often forceful case for that claim.

More than once In The Brewing Luminous reminded me of the writer’s skill in describing the tonal and textural qualities of rock and metal. Freeman can break down a riff into its component parts, and evoke the particular sensations of music washing over you. Taylor’s writing method involved what he called unit structures, and repetition with variation is a crucial aspect of his approach to the piano. It‘s not quite rock ‘n’ roll, but Freeman’s ear for minute changes in intensity and angle and attack give the book a crucial cutting edge, and anyone interested in the experience of extreme music will find a guide here who finds calm in the eye of the storm.

There’s currently a nice extract on The Wire’s site which details Taylor’s experience of finally playing with Elvin Jones, alongside Max Roach. Phil’s piece on Cecil Taylor can be found on the cover of The Wire 386, and you can read more about all his activities on his website.